Salt Lake City, Utah, April 8, 2025

Utah has become the first state to ban fluoride from its public water supply. While national headlines focus on the health freedom debate, a deeper and more consequential question is emerging: In an age of AI-driven water monitoring and IoT infrastructure, is the era of one-size-fits-all public health treatments over?

The new law, HB81, passed the Utah Legislature and was signed by Governor Spencer Cox in late March. It prohibits municipalities from fluoridating public water and instead broadens access to fluoride supplements that can be prescribed by pharmacists—no doctor required.

Supporters say the move is about personal choice. Critics warn it could reverse decades of dental health progress. But beyond the controversy lies a larger story—one about how technology is fundamentally reshaping the way we think about public health, utilities, and personal responsibility.

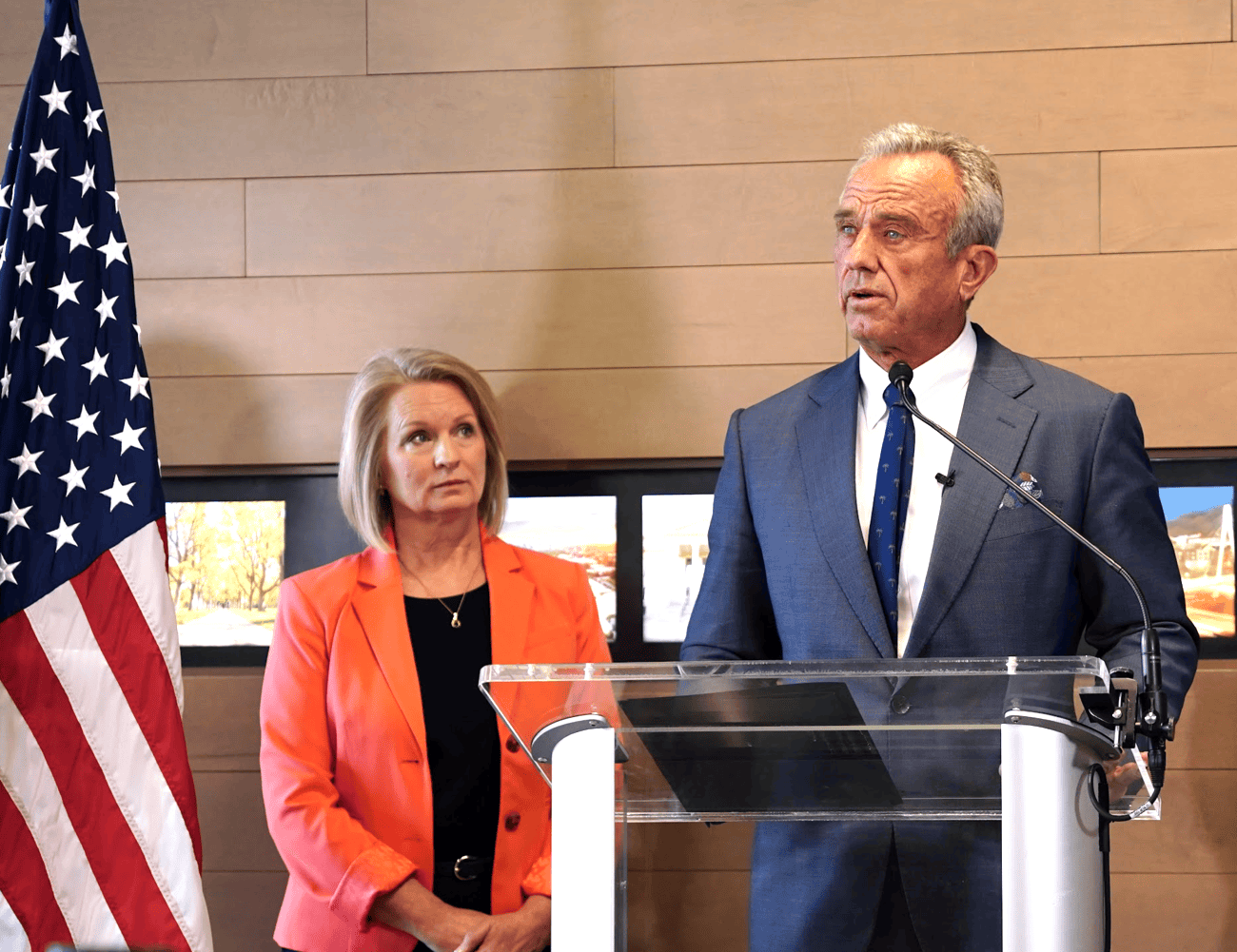

“We empower individuals to choose what they put into their bodies,” said Rep. Stephanie Gricius, co-sponsor of HB81, along with Sen. Kirk Cullimore (Districts 9 and 19). “This is the type of common sense policy that makes Utah the greatest state in the nation.”

Fluoridation began in the 1940s as a landmark public health intervention to reduce tooth decay, particularly among low-income populations. By chemically treating the shared water supply, cities could deliver benefits equitably and inexpensively. But that model was built for an era when utilities had no way to differentiate, adapt, or personalize exposure.

But that model assumes uniformity. It presumes that all individuals benefit equally from the same dosage. And it reflects a time when public utilities had little to no ability to adapt treatments based on real-time data.

Fast forward to today.

With the rise of IoT (Internet of Things) water sensors, AI-powered modeling, and smart utility management, communities can now monitor water quality, chemical concentrations, and exposure levels in real time. We're not just talking about detecting lead or bacteria—new systems can measure fluoride levels down to the household level, track trends, and even forecast potential health risks based on environmental and demographic data.

In other words: we no longer have to treat everyone the same.

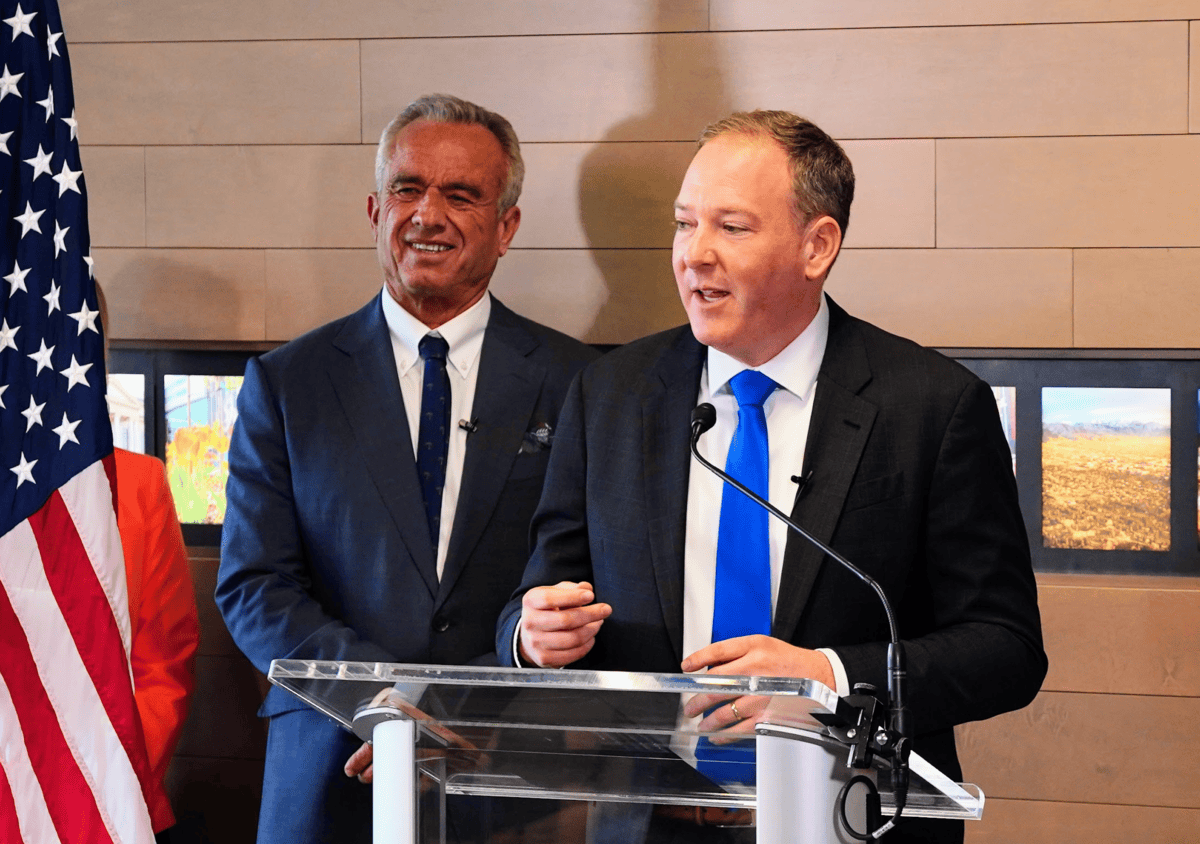

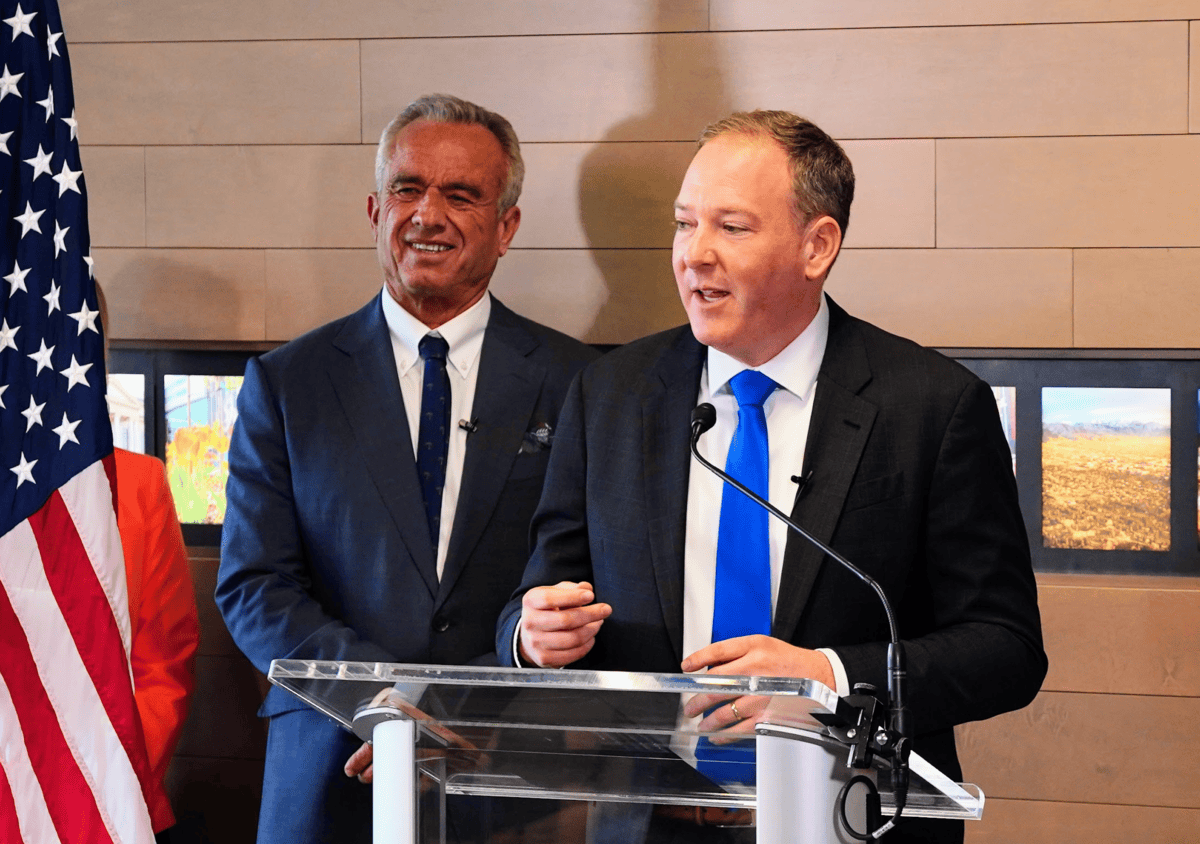

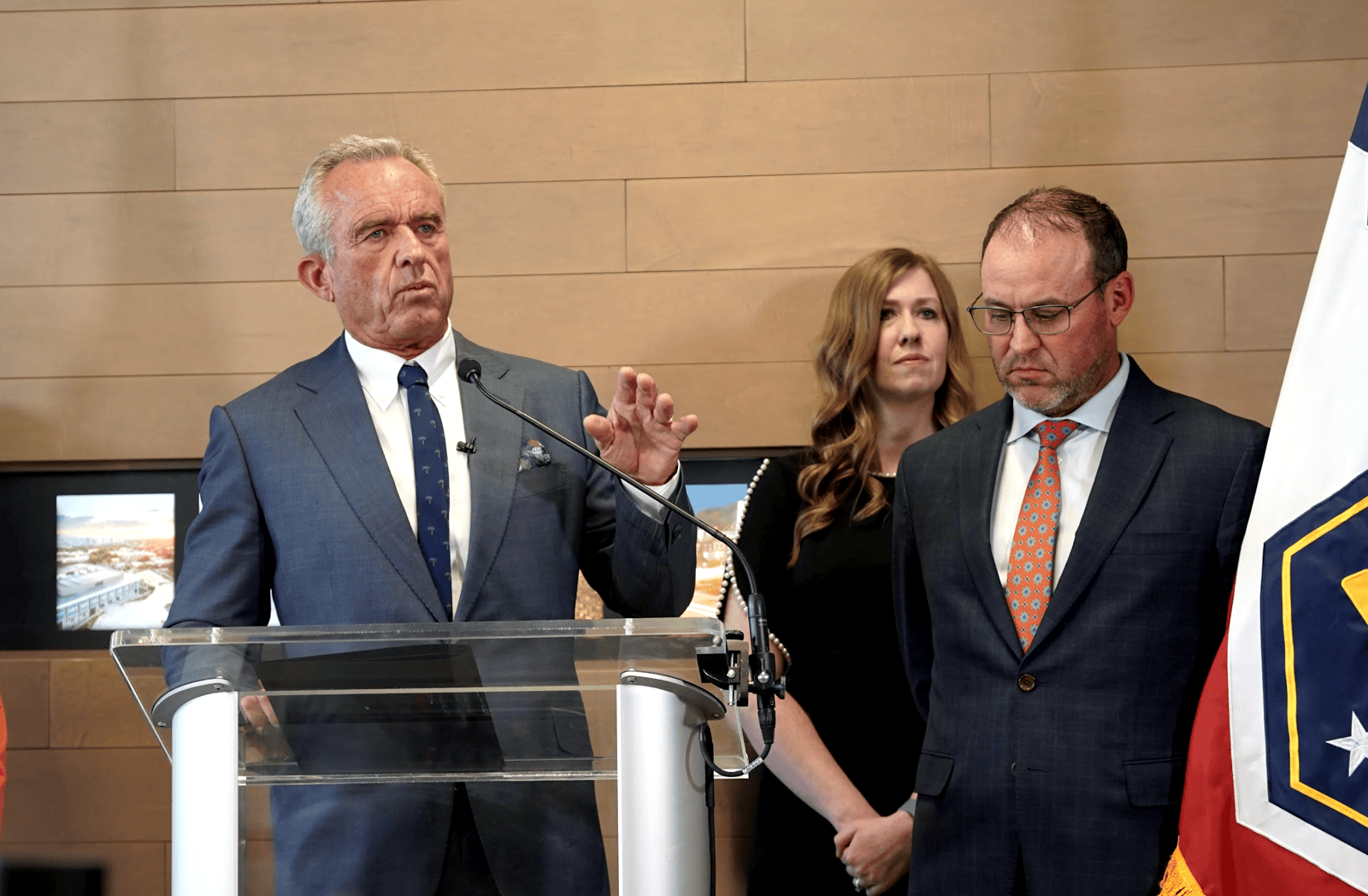

All of this innovation was quietly in the background as Utah’s top political leaders gathered at the University of Utah yesterday for a press conference announcing the law’s signing. HB81 sponsor Rep. Stephanie Gricius (District 50 - Utah County) was joined by U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin, Rep. Kristen Chevrier (District 54 - Utah County), and Utah House Speaker Mike Schultz (District 12 - Davis, Weber counties).

“I’m very proud of Utah,” said Kennedy. “It has emerged as the leader in making America healthy again.”

Kennedy, long known for his skepticism of mass fluoridation, cited findings from the National Toxicology Program linking systemic fluoride exposure to neurological, endocrine, and skeletal health risks. “The only benefit of fluoride is topical, not systemic,” he said. “There’s no reason to ingest it when brushing your teeth provides the same protection. The science hasn’t kept up with the technology.”

EPA Administrator Zeldin added that the agency would reopen its review of fluoride guidelines in response to these emerging studies. “If this is as important as it is to Secretary Kennedy—and clearly to so many people here in Utah—it is top of the list for the Environmental Protection Agency.”

And the federal government is watching. “The EPA is going back to look at all the studies that have come out since July 2024,” said Zeldin. “We’re prepared to act based on the science.”

Much of the public debate centers on health claims, but what’s less discussed is how technology is making personalized water treatment more feasible than ever before.

Here are a few innovations driving this shift:

- IoT Water Sensors: Installed at key nodes in water systems—or even inside homes—these sensors can track a wide range of contaminants, including fluoride, chlorine, nitrates, heavy metals, and pathogens. They transmit real-time data to municipal dashboards, alerting operators to quality changes instantly.

- AI Exposure Modeling: Using machine learning, utilities can now build dynamic models of chemical exposure, factoring in geography, population health data, and even behavior patterns (like whether households use filtration systems or bottled water). This enables targeted interventions rather than blanket policies.

- Smart Utility Platforms: Increasingly, water utilities are adopting AI-driven platforms that optimize treatment levels across different zones. This could allow one neighborhood to receive higher fluoride treatment—while another doesn’t—based on need or opt-in preferences.

- Consumer Access Dashboards: Some startups are even creating apps that let households track their water quality daily and make informed decisions about supplemental treatment.

Taken together, these technologies offer a future where mass chemical treatments are no longer the only viable option. Instead, public health could evolve toward “precision exposure”— targeting needs without compromising individual freedom or systemic safety.

Balancing Innovation, Ethics, and Access

The transition away from blanket fluoridation raises real concerns. Dentists and healthcare providers have warned that without it, low-income populations may suffer increased tooth decay and long-term dental costs. “The net result will be additional costs to Utah families,” said Lorna Koci of the Utah Oral Health Coalition. “We think the increase in decay will cause more children to be out of school and more people unable to work.”

Others argue that personalized tech may widen the health gap unless implemented equitably. IoT sensors and smart treatment systems don’t automatically reach underserved areas. And many families won’t have the time, resources, or knowledge to manage supplemental fluoride on their own.

That’s where thoughtful design—and public investment—comes in.

Utah’s law includes a key provision: fluoride supplements can now be prescribed directly by pharmacists. This reduces barriers and creates a potential blueprint for other states considering similar shifts.

A National Experiment in Public Health Tech

During the press event, Utah House Speaker Mike Schultz floated a broader idea: Let Utah serve as a national pilot for public health policy powered by local innovation.

“We manage more effectively, more efficiently, and more affordably than the federal government,” he said. “Let us be a national experiment.”

That sentiment aligns with Utah’s broader track record: top-ranked for business, upward mobility, and now—potentially—a pioneer in personalized water infrastructure.

As more states reconsider long-standing public health practices, Utah's fluoride law could become a case study in how data science and individual autonomy can work hand-in-hand.

What’s Next?

The future of water may not be about fluoride at all. It may be about choice, transparency, and customization—driven by smart tech and smart policy.

Will AI-powered monitoring replace blanket treatments? Will households become active participants in their own water health? Will states follow Utah’s lead, or double down on traditional models?

As other states consider following Utah’s lead—or doubling down on traditional models—the broader shift is clear. The era of passive public health is giving way to something more data-driven, decentralized, and customizable. Similar experiments are already underway in California, where the East Bay Municipal Utility District is piloting opt-in chemical treatments based on neighborhood input. In Colorado, Boulder is testing a machine learning platform to adjust water treatment levels dynamically by zone. And in Texas, Austin Water has partnered with researchers at UT Austin to study real-time exposure management through smart meter data. Beyond these technological initiatives, several regions have taken legislative action to remove fluoride from public water systems. For instance, Miami-Dade County, Florida, voted to stop adding fluoride to its public water supply in April 2025 (ABC News). Similarly, Union County, North Carolina, and Collier County, Florida, prohibited the addition of fluoride to their drinking water in early 2024 (Stateline). The future of public infrastructure may not be about adding more chemicals. It may be about delivering precision—and choice.

But one thing is clear: The era of passive public health may be giving way to something far more dynamic, decentralized, and data-driven.

And Utah, once again, is right at the center of it.